Finger pointing

we have the power to shift our perspective, are we using it?

Did you know that what your eyes see is not what your brain sees? (Can we believe our eyes?) Yep, groups I talk to are skeptical, too, so we play a game. It looks like this:

The Brain Game

The rules of the game are: pick a linear object in the distance (a tree, a cabinet door, a shelving unit, etc.) and, with your arm extended, line your finger up with that line. Do this with both eyes open while keeping your focus on the distant linear object. Do it quickly. Don’t’ think too hard about it.

Now: close your right eye. (does your finger move?) Now: close your left eye. (does your finger move or stay?) Most people see their finger move with one eye open and stay with the other. The eye open when the finger doesn’t move is said to be your “dominant” eye and the side of the brain (hemisphere) opposite this side is said to be your dominant side. Thus, right eye open, left brain dominant and the converse.

People are astounded by this experience. As they well should be, because it is miraculous. But why? (Here’s where, if you want to skip the science, scroll down to the Message Behind the Miracle.)

Vision Explained

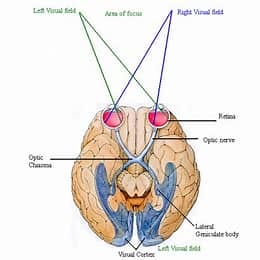

When you look at something through your two eyes (for those of us blessed with binocular vision), you are actually seeing it two ways, one way through your right eye and one way through your left eye. The light input comes at a slightly different angle by each.

The color and shape of what our eyes are seeing travels as light signals through separate optic nerves, one on each side of the brain. The nerves carrying this information actually each cross onto the other side of the brain and send this information to the visual cortex of the brain on that side. Thus, we get two slightly different representations of what we are seeing communicated to our brain.

Our brains then (very quickly) compare the two images and — without negating either — decide which one “to believe.” If you have now tried this exercise for yourself, as I hope you have, you will realize that you still have both inputs available, but one predominates. If you then shift your focus from the distant linear object to your nearby finger, you’ll see you still have only one finger and, oddly enough, it may have moved as your brain struggles to “decide” which side of the brain to believe.

So, why in the world do we have this redundancy of visual input? Why not just one eye, one image, one sight? The answer: so we can have depth perception. By comparing the two images, our brain is able to gauge distance and dimension. This is good for shooting a basketball and for deciding whether to run from approaching danger. And we fine tune this with practice.

Mirculous, right?

And yes, visual anatomy varies within our species and among different species. This effects the operation of the system and even dictates when other anatomical changes or behavioral changes are needed to supply visual information. (Nerd tidbit: Owls, for instance, have heads that swivel almost 270 degrees to accommodate the placement of their eyeballs and their nocturnal hunting practices.)

One more thing. Visual input which enters the eyes doesn’t just switch sides as it enters the brain, it inverts. That is, input at the top of our visual field travels to the bottom of our eyeball and input at the bottom travels to the top.

The result: the visual image sent to our brains is upside down and backwards. It is then up to our brains — as our organs of making sense of stuff in the world — to learn (by trial and error) which way is up and which side is right or left. Otherwise, we could not coordinate picking up a cup or striking the correct key on our keyboard accurately. Ever.

(Nerd tidbit 2: They’ve tested this visual field righting ability in studies where subjects wear glasses that invert the images they see. Over a few days, subjects (re-)learn to see things right-side up even with the upside-down glasses on. How fast they learn to right things depends on how much they are allowed to physically interact with their environment. For instance, being in a wheelchair or wearing mittens impedes the righting process; while walking and touching things speeds it up.)

Geez… When I consider the trouble my body goes to allow me to see and decide what I’m seeing, all in a split second, and to judge distance and direction nearly as fast, I am wowed. The process, then, of deciding what to make of what I see — which is more complex still — will have to wait for another post. But trust me: it’s gobsmacking.

Message Behind the Miracle

So here we have an amazing sensory system we call vision with complexities almost beyond our comprehension, yet it operates smoothly and systematically almost without fail. (Aging and eyesight notwithstanding, but correctible by a good optometrist.) If you’re like me, you don’t think much about it. You take it for granted.

So, what does the visual brain teach us about being Fit2Finish in life?

We humans are sided creatures; that is, we prefer to use our right or our left to do things. Even ambidextrous individuals generally have a preferred side. Our new understanding of vision has us wondering … is the right really right or is it left? Is top really top or is it bottom? Is first actually first or is it last?

Vision teaches us we need to:

test what we see

use all of our input

engage with our environment with all of our senses

process incoming information in light of this input

Then we compare our conclusion to what we have already learned and see if it makes sense. Even then, we may be misled if we’re not open-minded. Because the amazing truth our visual system illuminates is this:

We are creatures of our own perceptions.

What I see, perceive, understand, relate to and retell as part of my story, is based on what I witness. What you see is different. It has to be because you’re looking at it differently. So, the best version of what truly is, is the collective vision we all see.

With patience, humility, understanding, and a dab of science, we stand before the miraculous creations we are and are mindful. We may be left-brained; we may be right-brained, but together we’re whole-brained. A whole humanity with a lot to learn.